NEW MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN WARSAW IS OPEN

In Warsaw, a new building for the Museum of Modern Art has opened. This moment marks both the culmination of long-standing efforts to create a new space for contemporary art and the beginning of an exciting chapter in its evolving future. The museum, aiming to shape the image of contemporary art through its exhibition program and declared openness, fulfills an almost century-old desire for modern art to have its place in the heart of Warsaw.

In light of comparisons of its architecture to the shape of a box, let’s consider it as a “white box”—a model space for presenting modern art. Despite some criticism, using the simple external walls as screens is a straightforward and, in its simplicity, successful idea that allows the collection to “emerge” outside, democratizing access to art. However, additional questions are worth asking. How does the building respond to the challenges of climate change? Were tools utilized to minimize its negative environmental impact? Will it truly be accessible—for example, to people with limited mobility?

Minimalist Architecture and a Challenging Location

The new building, designed by Thomas Phifer & Partners, sparked much emotion even before its opening. Warsaw residents quickly dubbed it a “distribution warehouse” in the city centre. Critics reference its simple exterior form and perceived mismatch with the urban context, labelling it as lacking an avant-garde character. In recent years, so many stunning, unique buildings have been created worldwide that it is difficult to compare the Warsaw museum to them. From this perspective, perhaps is the intended minimalism a justified choice?

The building is situated near the Palace of Culture and Science and across from the illuminated former Central Department Stores—a choice that is no coincidence; the museum is intended to become a key point on the city’s artistic map, with its architecture reflecting a dynamic dialogue between past and present. The immediate surroundings are revitalized—the small architectural elements and greenery outline the area’s pre-war street layout. One should remember that the vast Parade Square was built over a sea of ruins from streets like Świętokrzyska, Złota, and Chmielna destroyed in the II World War.

A Story of Dreams and a Realistic Concept

The need for a museum of modern art in Warsaw has been raised since the 1970s. Artists’ voices were among those calling for it. Marian Bogusz advocated that the museum should be close to the people and actively participate in the life of the city. His vision proposed a museum as a “living organism,” responsive to the needs of artists and audiences. Aleksander Kobzdej, an artist with a complex biography (he created the famous painting Podaj cegłę (Hand Me the Brick) before becoming an avant-garde figure), saw the need for a space to engage openly with Western art.

Modern approaches to art demand interaction with the public. This fits global trends where art is not just an object to observe but a space for creative exchange that often addresses the most pressing contemporary issues.

Challenges and Controversies

The current museum project began in the early 21st century, with initial steps taken in 2005 when an architectural competition was announced. I remember my sister Magda’s excellent project from those days, with which she graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. Her museum design would have been near Karowa Street, integrated into the greenery and connecting Krakowskie Przedmieście with the Vistula River. After several years of attempting to realize Swiss architect Christian Kerez’s design, the work was eventually entrusted to New York’s Thomas Phifer & Partners. The new museum is intended as a space open to the city, combining various art forms and engaging the community.

The museum’s interior is impressive. During the opening night on October 24, 2024, it was filled with guests. I listened with curiosity to their comments. Undoubtedly, the vast space makes an impact. The immaculate white stairs are spectacular, reminiscent of a “squared-off” reference to the iconic New York Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright. In the Guggenheim, the corridors and stairs enhance comfort for visitors, connecting the floors seamlessly and, as seen online, providing excellent photo opportunities. The contrast between the white interior and the black dots of people moving near the imposing staircase can be seen as a nod to New York’s spiral building. But will it prove similarly functional and resilient over time?

Incidentally, it’s worth mentioning that the Guggenheim collection includes works by the mentioned Aleksander Kobzdej, and Polish artists dreaming of museums in Warsaw or Łódź could become acquainted with such impressive architecture during brief interactions with the outside world.

The Bilbao Effect

Without a doubt, the ambition to achieve the “Bilbao Effect” often accompanies the creation of new museums. The Guggenheim’s branch in the Basque city, a breathtaking and otherworldly building by Frank O. Gehry, revitalized the local economy. Through the Guggenheim Foundation, the city emerged from economic decline.

The Vanishing Emilia, Warsaw Fogs

The Museum of Modern Art’s opening took place on a cool, foggy day. A white veil enveloped Warsaw, obscuring the Palace of Culture and transforming the neon lights of the city centre into blurred coloured dots. The fog also enveloped the museum building. This reminded me of a foggy March day when the deconstruction of the former Emilia Pavilion—a vibrant and effective temporary home for the museum—began. Emilia was, of course, not suited for displaying contemporary art. However, it fulfilled a key goal architects should consider today: the environmental impact of new buildings. We should seek ways to “recycle” buildings, which can take creative forms through “upcycling.” New uses for old buildings add meaning and splendour, and modern art can sometimes complement historic architecture well. I recently saw this in Vilnius, where vibrant art galleries operate in former factories and partially restored interiors of the Sapieha and Radziwiłł palaces.

In this context, it’s essential to ask how the new museum building responds to contemporary challenges. These are beautifully defined by the New European Bauhaus idea, which envisions architecture that ensures beauty, sustainability, and inclusivity—a triad that subtly modifies Vitruvius’s utility, durability, and beauty (utilitas, firmitas, venustas).

Ecology and Inclusivity

Beauty can be a subject of debate and controversy. Opinions may differ. However, sustainability and accessibility for all should not be negotiable. These two elements are part of the museum’s declared goals, and I hope that the museum, along with its creative team, will actively seek ways to integrate the promotion of new art with responses to climate concerns and aspirations for democratizing art.

This, in my view, is the greatest challenge.

I will certainly visit the new institution frequently—not only for the announced exhibitions (I’m curious to see how Edward Dwurnik’s work will be presented at one of the upcoming exhibitions) but also to check whether the spacious interiors, multi-story doors, and scattered skylights and windows provide comfort and accessibility for visitors (young and old, diverse…) without the need for excessive heating, lighting, and cooling—luxuries that art institution, facing contemporary climate challenges, cannot afford.

The museum needs time to prove its value and significance in the cultural landscape of the capital. It faces the challenge of meeting the expectations of both artists and the public. Its success depends on whether it can become a lively space for exchange, inspiration, and interaction—for everyone.

Women Artists in the Museum

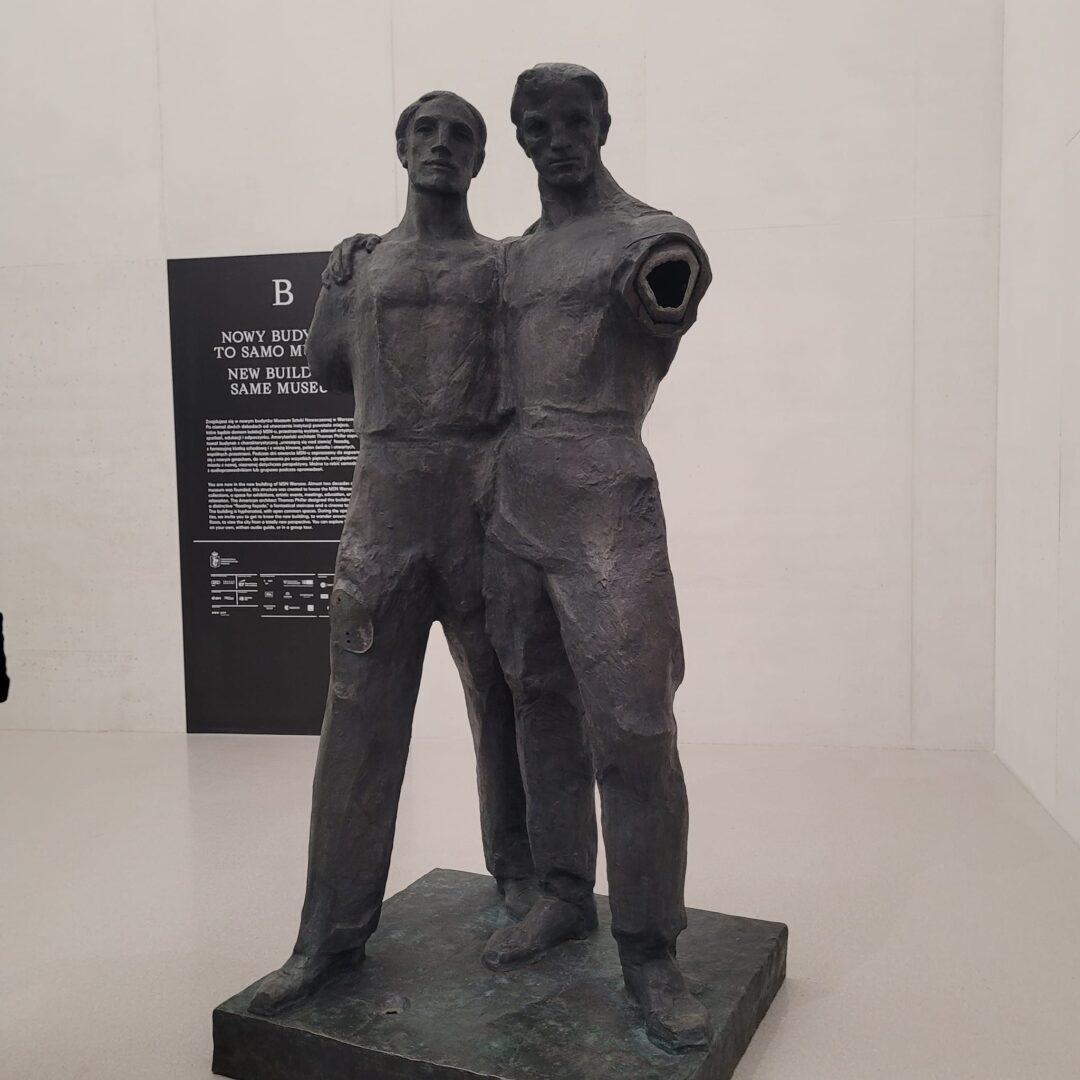

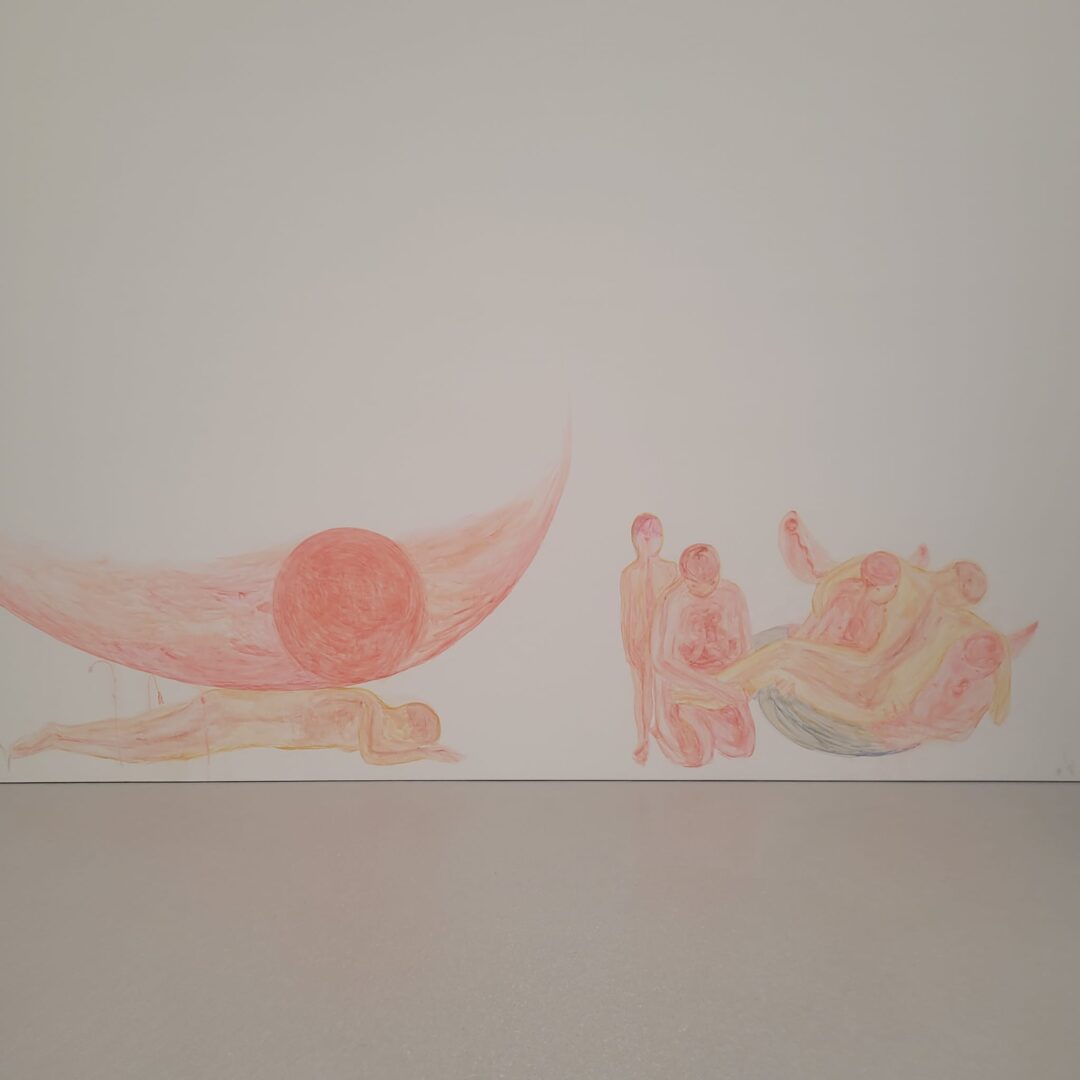

The opening exhibition is more than promising. I am impressed by what is most important in a museum—the remarkable works. By focusing on women’s art, the museum seeks to fill an existing gap. The opening vernissage provided an opportunity to see the spectacular Abakans, a dramatic installation by Congolese artist Sandra Mujinga, Monica Sosnowska’s work reminiscent of a trace of disaster, and a powerful asphalt sphere by acclaimed Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova, addressing the issue of the Anthropocene.

Now I look forward to more, and wishing Warsaw flourishing tourism, I hope the vision shaped amidst tensions, controversies, and sometimes warranted fears and criticism will prove itself over time. This will require much work, passion, and openness.

Justyna Napiórkowska, Geneva, October 26, 2024

P.S. A longer text of mine will be published in the anniversary edition of ArtPost magazine.

NEW MUSEUM OF MODERN ART IN WARSAW IS OPEN

In Warsaw, a new building for the Museum of Modern Art has opened. This moment marks both the culmination of long-standing efforts to create a new space for contemporary art and the beginning of an exciting chapter in its evolving future. The museum, aiming to shape the image of contemporary art through its exhibition program and declared openness, fulfills an almost century-old desire for modern art to have its place in the heart of Warsaw.

In light of comparisons of its architecture to the shape of a box, let’s consider it as a “white box”—a model space for presenting modern art. Despite some criticism, using the simple external walls as screens is a straightforward and, in its simplicity, successful idea that allows the collection to “emerge” outside, democratizing access to art. However, additional questions are worth asking. How does the building respond to the challenges of climate change? Were tools utilized to minimize its negative environmental impact? Will it truly be accessible—for example, to people with limited mobility?

Minimalist Architecture and a Challenging Location

The new building, designed by Thomas Phifer & Partners, sparked much emotion even before its opening. Warsaw residents quickly dubbed it a “distribution warehouse” in the city centre. Critics reference its simple exterior form and perceived mismatch with the urban context, labelling it as lacking an avant-garde character. In recent years, so many stunning, unique buildings have been created worldwide that it is difficult to compare the Warsaw museum to them. From this perspective, perhaps is the intended minimalism a justified choice?

The building is situated near the Palace of Culture and Science and across from the illuminated former Central Department Stores—a choice that is no coincidence; the museum is intended to become a key point on the city’s artistic map, with its architecture reflecting a dynamic dialogue between past and present. The immediate surroundings are revitalized—the small architectural elements and greenery outline the area’s pre-war street layout. One should remember that the vast Parade Square was built over a sea of ruins from streets like Świętokrzyska, Złota, and Chmielna destroyed in the II World War.

A Story of Dreams and a Realistic Concept

The need for a museum of modern art in Warsaw has been raised since the 1970s. Artists’ voices were among those calling for it. Marian Bogusz advocated that the museum should be close to the people and actively participate in the life of the city. His vision proposed a museum as a “living organism,” responsive to the needs of artists and audiences. Aleksander Kobzdej, an artist with a complex biography (he created the famous painting Podaj cegłę (Hand Me the Brick) before becoming an avant-garde figure), saw the need for a space to engage openly with Western art.

Modern approaches to art demand interaction with the public. This fits global trends where art is not just an object to observe but a space for creative exchange that often addresses the most pressing contemporary issues.

Challenges and Controversies

The current museum project began in the early 21st century, with initial steps taken in 2005 when an architectural competition was announced. I remember my sister Magda’s excellent project from those days, with which she graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Warsaw University of Technology. Her museum design would have been near Karowa Street, integrated into the greenery and connecting Krakowskie Przedmieście with the Vistula River. After several years of attempting to realize Swiss architect Christian Kerez’s design, the work was eventually entrusted to New York’s Thomas Phifer & Partners. The new museum is intended as a space open to the city, combining various art forms and engaging the community.

The museum’s interior is impressive. During the opening night on October 24, 2024, it was filled with guests. I listened with curiosity to their comments. Undoubtedly, the vast space makes an impact. The immaculate white stairs are spectacular, reminiscent of a “squared-off” reference to the iconic New York Guggenheim Museum by Frank Lloyd Wright. In the Guggenheim, the corridors and stairs enhance comfort for visitors, connecting the floors seamlessly and, as seen online, providing excellent photo opportunities. The contrast between the white interior and the black dots of people moving near the imposing staircase can be seen as a nod to New York’s spiral building. But will it prove similarly functional and resilient over time?

Incidentally, it’s worth mentioning that the Guggenheim collection includes works by the mentioned Aleksander Kobzdej, and Polish artists dreaming of museums in Warsaw or Łódź could become acquainted with such impressive architecture during brief interactions with the outside world.

The Bilbao Effect

Without a doubt, the ambition to achieve the “Bilbao Effect” often accompanies the creation of new museums. The Guggenheim’s branch in the Basque city, a breathtaking and otherworldly building by Frank O. Gehry, revitalized the local economy. Through the Guggenheim Foundation, the city emerged from economic decline.

The Vanishing Emilia, Warsaw Fogs

The Museum of Modern Art’s opening took place on a cool, foggy day. A white veil enveloped Warsaw, obscuring the Palace of Culture and transforming the neon lights of the city centre into blurred coloured dots. The fog also enveloped the museum building. This reminded me of a foggy March day when the deconstruction of the former Emilia Pavilion—a vibrant and effective temporary home for the museum—began. Emilia was, of course, not suited for displaying contemporary art. However, it fulfilled a key goal architects should consider today: the environmental impact of new buildings. We should seek ways to “recycle” buildings, which can take creative forms through “upcycling.” New uses for old buildings add meaning and splendour, and modern art can sometimes complement historic architecture well. I recently saw this in Vilnius, where vibrant art galleries operate in former factories and partially restored interiors of the Sapieha and Radziwiłł palaces.

In this context, it’s essential to ask how the new museum building responds to contemporary challenges. These are beautifully defined by the New European Bauhaus idea, which envisions architecture that ensures beauty, sustainability, and inclusivity—a triad that subtly modifies Vitruvius’s utility, durability, and beauty (utilitas, firmitas, venustas).

Ecology and Inclusivity

Beauty can be a subject of debate and controversy. Opinions may differ. However, sustainability and accessibility for all should not be negotiable. These two elements are part of the museum’s declared goals, and I hope that the museum, along with its creative team, will actively seek ways to integrate the promotion of new art with responses to climate concerns and aspirations for democratizing art.

This, in my view, is the greatest challenge.

I will certainly visit the new institution frequently—not only for the announced exhibitions (I’m curious to see how Edward Dwurnik’s work will be presented at one of the upcoming exhibitions) but also to check whether the spacious interiors, multi-story doors, and scattered skylights and windows provide comfort and accessibility for visitors (young and old, diverse…) without the need for excessive heating, lighting, and cooling—luxuries that art institution, facing contemporary climate challenges, cannot afford.

The museum needs time to prove its value and significance in the cultural landscape of the capital. It faces the challenge of meeting the expectations of both artists and the public. Its success depends on whether it can become a lively space for exchange, inspiration, and interaction—for everyone.

Women Artists in the Museum

The opening exhibition is more than promising. I am impressed by what is most important in a museum—the remarkable works. By focusing on women’s art, the museum seeks to fill an existing gap. The opening vernissage provided an opportunity to see the spectacular Abakans, a dramatic installation by Congolese artist Sandra Mujinga, Monica Sosnowska’s work reminiscent of a trace of disaster, and a powerful asphalt sphere by acclaimed Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova, addressing the issue of the Anthropocene.

Now I look forward to more, and wishing Warsaw flourishing tourism, I hope the vision shaped amidst tensions, controversies, and sometimes warranted fears and criticism will prove itself over time. This will require much work, passion, and openness.

Justyna Napiórkowska, Geneva, October 26, 2024

P.S. A longer text of mine will be published in the anniversary edition of ArtPost magazine.